Fish in the Bay – October 2019, UC Davis Trawls – Winter Fish Arrivals & a goby surprise.

I joined the UC Davis trawls on both days of this October’s trawling weekend. … Fish are on the move! They know the weather is changing.

Trawl map

Bay-side station trawling results.

Upstream of Railroad Bridge.

One thing to note before we get into the fish discussion: time of day has a big influence on Dissolved Oxygen (DO) concentrations. Now that we record time, instead of tide, in the second row near the top of the tables, you can see that DO tends to be lower during morning hours (particularly at 8:25 AM in Pond A19) and higher in the afternoon.

As everyone knows, phytoplankton need sunlight to photosynthesize and produce oxygen. They have to rise and shine like all the rest of us!

1. Winter Fish are Returning

American Shad. Eight of these delicious fish showed up in October. (Their scientific name “Alosa sapidissima” literally means “the delicious (or savory) shad.”) Seals and porpoises also like to eat them!

We had only seen seven (7) of these beauties since the beginning of April. These non-native fish migrate out to sea during warm months, then return to creeks in wintertime to spawn. Now, they are returning.

Bronze-colored American Shad from Art2 on 6 October.

American Shad dorsal color seems to change very rapidly in response to water conditions:

- When caught in fresher water further upstream American Shad dorsal color invariably looks brownish-bronze.

- Closer to the Bay, they appear blue-green.

I never seem to find a bronze one downstream, nor a blue-green one upstream. I surmise that American Shad have a high degree of “color plasticity.” Salinity must be the operative factor. (If temperature was the cause, we would see only blue-green shad in winter and bronze shad in summer.)

The countershading color change helps camouflage the fish; ocean water tends to be clear and blue, creek water is turbid and brown. But, how does salinity change the arrangement of guanine crystals in iridophores along this shad’s back? And, how does it happen so quickly? (These are biochemistry questions.)

And, why does the color change similarly, but NOT so quickly, in the other related “Clupeiform fishes” (https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Clupeiformes) like Northern Anchovies and Pacific Herring?

Pacific Herring. This was the only Herring caught this month, but the first one ever caught in an October in over 5 years of UC Davis trawls. Like the three other juvenile herring caught last month, it indicates that Herring have become more common in Alviso marshes with wetter winters.

Herring dorsal colors also range from blue-green to bronze, like the shad. Unlike shad, Herring color appears to be a little more fixed. I have photographed blue-green herring farther upstream, and bronze ones closer to the Bay. Albeit, my Herring sample size is very small to date, and I have not examined any adults.

Four Longfin Smelt caught in October.

Longfin Smelt are starting to return to the Alviso marshes for spawning as well. Hooray!

Wintertime Fish Chart: Shad, Herring, & Longfin Smelt.

As previously noted, Shad, Herring, & Longfin Smelt numbers substantially increased after the Freshwater Flush of 2017. These types of fish spawn and recruit in, or near, flushing creeks. Wet winters and strong pulses of creek flushing boost their populations. Here’s the proof!

Based on this historic trend, we should expect to see the highest numbers of all four species after December.

2. Baby Fish Explosion

“Unidentified Gobies” (222 of them) were caught this weekend. These are young juveniles, roughly 5 to 10mm, just past yolk sac stage. This is unusual for an October.

Over the last 5 years our annual Baby Fish Explosion happened in April (2014, 2016, 2017, and 2019) or July (2018). We presume that most baby fish are the invasive and hated Yellowfin Gobies because spring-to-midsummer “Peak Yellowfin Goby” usually corresponds closely with “Peak Baby Fish.”

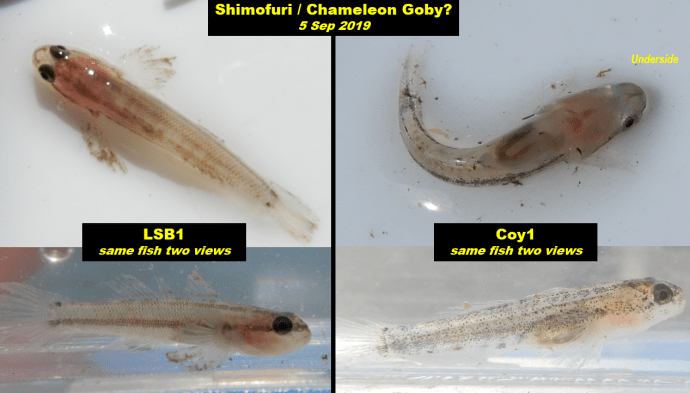

Baby fish from station Coy2. A slightly older juvenile Shimofuri/Chameleon Goby is shown in bottom right panel.

This baby fish explosion is different. Many of these babies show a pinkish area just behind the head and longitudinal stripes passing through the eyes and extending to the tail. These stripes are characteristic of young Shimofuri or Chameleon Gobies.

In the past, most baby fish were clear bodied and fairly unidentifiable to the naked eye.

Baby fish closeup – Coy2

Baby fish at Coy3

All these baby fish were counted as “Unidentified Goby.” It was a mixed bag. There were many clear-bodied Yellowfins(???), along with one or two dark-banded Shokihazes, and many longitudinal striped Shimofuri/Chameleons.

Longitudinally-striped babies like these were not noticed in previous baby fish events.

More baby fish closeups.

The consistency of appearance was a bit shocking. Striped baby fish were observed in Pond A21, at all stations in the main stem of Lower Coyote Creek (stations Coy1, Coy2, Coy3, Coy4), way out in the deep Bay at LSB1, and far upstream at DMP2.

- Are we witnessing a Shimo/Chameleon Goby explosion?

Micah Bisson setting the net at DMP2

Yet another baby Shimo/Chameleon Goby from DMP2

This adult Shimofuri was caught at station Art2. The anal fin appears to have a stipe that is a little more orange than white, but it is hard to tell.

Numbers of Shimofuri/Chameleon Gobies in LSB steadily increased from three in 2014 to 263 in 2018. The 2019 count is still a little low, at 77, but this current spawning event could lead to more. Who knows?

Reminder: Shimofuris are practically indistinguishable from Chameleon Gobies.

- Shimos adults have an ORANGE stripe on the anal fin. They tend to inhabit the North Bay and Delta since their invasion in 1985.

- Chameleons adults have a WHITE stripe on the anal fin. They predominate in Central and South Bay (no one knows why) since their 1978 invasion.

- Abdicated Japanese Emperor Akito is the world’s expert on identifying these gobies. Steven Slater is our local expert, mainly regarding Shokihaze Gobies. (See Fish in the Bay – July 2019 report: http://www.ogfishlab.com/2019/07/14/fish-in-the-bay-july-2019-uc-davis-trawls-brown-back-anchovies-and-bat-rays/)

- I must caution that all baby Shimo/Chameleon Gobies were thus far identified by non-laboratory eyeball examination. – Also, as far as we know, no baby fish were harmed by this examination!

Goby / Unidentified Baby Fish table – raw fish counts, 2014 numbers adjusted for 5-minute trawls.

Goby Table. The table above shows raw counts of Gobies (four types) plus Unidentified baby fish. A few things pop out:

- Yellowfin Gobies are our most numerous Goby and top invasive fish. They invaded SF Bay sometime in the 1970s through 1980s.

- Yellowfin Goby numbers surged around April to July as regular as a heartbeat in each of the previous five years, 2014 through 2018. (No big surge in 2019 though!)

- Unidentified / Baby Fish also spiked around the time of the Yellowfin Goby surge in all years except 2015. We assume that most unidentified baby fish each year were baby Yellowfins.

- An unprecedented Shimofuri and Shokihaze Goby spawning event was detected in December 2018: 210 Shimos, 200 Shokihazes were caught at station LSB2. Almost all were young.

Please note. In 2014 all otter trawls were 5 minutes in duration versus 10 minutes since then. I doubled all 2014 catch numbers so that the rough relative “Catch Per Unit Effort” (CPUE) would be consistent.

3. More Gobies: Arrows & Cheekspots.

I photographed a few more Arrow Gobies caught in Pond A21 – because we like them.

This Cheekspot Goby was caught in LSB.

4. Anchovy Color Studies – continued.

Faded Green-back from Dump Slough.

Northern Anchovy numbers dropped to only 66 in October. This is typical. Anchovies are usually thought of as a summer-time fish, and numbers do drop about this time of year. (Ironically, we saw a second big “spike” in Anchovy numbers in December-January of 2013/14, 2015/16, and 2018/19. But, more about that another time.)

More importantly, what are anchovies doing here after October? According to literature, Anchovies along the California Coast and in the Bay migrate back to the ocean during the winter. We know this is not true of all SF Bay Anchovies. As we learned again last January (and even as far back as October 2016, see http://www.ogfishlab.com/2016/10/01/fish-in-the-bay-1-october-2016-uc-davis-trawl-sharks/) many of these Anchovies must be spawning in the Bay.

- How many of these are ocean migrants versus year-round-residents?

- Are there distinct and separate Anchovy populations?

- What are they eating?

- etc.

Golden-green backed anchovies from Pond A21.

Like the Shad and the Herring, Anchovies have a very noticeable dorsal color gradient ranging from blue or green to gold.

- Unlike Shad, some Anchovies appear to lose dorsal color altogether becoming brown or clear/colorless.

- Unlike Shad, Anchovy colors do not change rapidly in response to environmental conditions. Vivid green and blue Anchovies have often been caught far upstream. Clear/colorless and even brown anchovies are often seen close to, or in, the deep Bay. And,

- Unlike Shad, there seem to be “tribes” or “races” (per Hubbs 1925) of Blue, Green, and Brown Anchovies.

Will we ever unravel this Anchovy Color Mystery? – Trust me, we shall!

As noted last month, we currently see an Anchovy gradient ranging from Golden-Green dorsal color upstream to Bluer and Clearer closer to, and in the deep Bay.

Young, nearly colorless blue-backs from LSB1 and LSB2.

Many of the deep Bay anchovies only show blue color and have little or no green.

More colorless blue-backs from LSB2.

I think the blue and green pigmentation is genetic. We have seen surges of vivid and uniformly blue OR green-backed anchovies in the past, e.g. see http://www.ogfishlab.com/2018/06/16/fish-in-the-bay-16-17-june-2018-uc-davis-trawls-yellowfin-gobies-strike-back/. Vividly colored Anchovies seem to migrate in from the ocean during warmer months, and that would be consistent with most Anchovy literature.

However, most Anchovies caught in LSB do not show vivid green or blue dorsal color most of the time. It seems to me both blue-backed and green-backed Anchovies loose dorsal pigmentation if they spend much time in the Bay. Anchovies that recruit in the Bay rarely develop any color at all.

- Blue-back Anchovies become clear/colorless or silvery.

- Green-back Anchovies transition to gold, and then brown/pinkish in absence of dorsal color.

One blue-green and one golden-green Anchovy from the mouth of Alviso Slough.

See what I mean? Anchovy color transitions back to warmer green tones as we progress up Alviso Slough.

However, we often find some blue-green Anchovies as well which indicates that the blue and green separation is not quite so distinct, or perhaps there is some in-Bay hybridization going on.

One vivid Green-back Anchovy was caught amongst the golden-greens at Alv2.

I would expect Anchovies to become more golden-green farther upstream, but this is not always the case. Once again, we caught a vivid green-back on October 5th. Is this odd-ball a recent migrant from the Pacific?

All Anchovies caught in Artesian Slough on 5 October were golden or brown.

Anchovies caught in Artesian Slough in October were very golden to brown. Artesian Slough tends to be a little more consistently fresh owing to discharge from the SJ/SC Regional Wastewater Facility.

This last example has all the traits of a classic Brown-back Anchovy: Brown/colorless back + shorter, deeper body + large head in comparison to body length. The faint trace of dorsal pigmentation appears gold with just a hint of green. If Carl Hubbs had seen this fish in 1925, he would have called it a Brown-back.

I will leave it at that for now. … There is much more to report from October:

- We caught a White Sturgeon just downstream of the San Jose-Santa Clara Regional Wastewater Facility on 6 October.

- Exopalaemon shrimp declined (a bit), and Crangon came back up (a bit).

- California Bulrush seems to have established a permanent colony in Pond A19, and more.

But, I must save it for another report.

Previous Post

Previous Post Next Post

Next Post