Fish in the Bay – August 2019, UC Davis Trawls – Worm Fight and the Evolving Marsh.

We had another good trawling weekend in August despite warm water and plummeting Dissolved Oxygen (DO).

Dr. Hobbs joined us despite his new job at Calif. Dept of Fish & Wildlife in Stockton.

Dr. Levi Lewis is now “Principal Investigator” and in charge of the UC Davis Biogeochemistry & Fish Ecology Lab. I imagine other changes will be coming (like a change of the name, from “Hobbs Lab.”) but so far, from my on-the-boat-perspective, Lower South Bay trawls continue as normal as we enter the 10th year.

Trawl map.

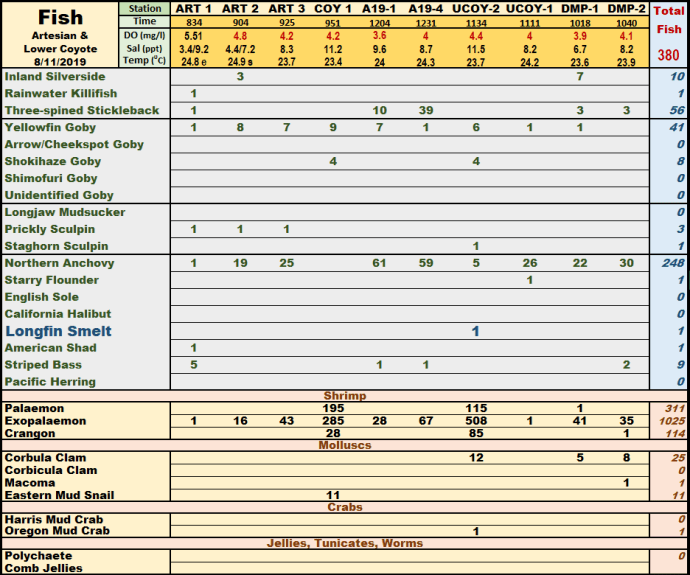

Bay-side station trawling results.

Note: I changed “Tide” to “Time” near top row. The row now shows the time each trawl started in 24-hour format. This is more useful. Anyone can figure out tide stage on any date and time from the NOAA Tides and Currents program.

I take hundreds of photos each trip. As long as each picture is filed in sequence, or carries a timestamp, photos can be matched to each of the 10 stations that date. … A future database will allow a user to quickly link dozens of fish and bug photos from each trawl.

Upstream of Railroad Bridge.

Low DO almost across the board on Sunday: Pond A21 also had low readings (below 5.0 mg/l) on Saturday as well.

Low DO correlates with warm summer temperatures and high marsh productivity. Phytoplankton photosynthesis pumps oxygen into marsh waters. Respiration by aerobic bacteria and all other animals, suck oxygen out of the water. We can expect that marsh DO drops even lower late at night when photosynthesis shuts off – this is a well-documented phenomenon seen in continuous water quality monitoring in this area.

As usual, the diversity of fish and bug life does not seem to be strongly affected by daytime DO down into the low “4s.” Species we typically think of as sensitive to low DO, Striped Bass, Longfin Smelt, and Northern Anchovies were, likely as not, caught where water was well below the 5.0 mg/l benchmark this weekend.

L to R: Micah Bisson looks on as Jim Hobbs sacrifices the sprinkle donut to the Sea Spirits.

Pat Crain drives the boat.

1. Speaking of Longfin Smelt, Anchovies, and low DO …

Longfin Smelt caught on Saturday: 77.9 degrees F

Longfin Smelt! This is the first time Longfins have been caught in a June, July, or August in several years of trawling. It should have been way too warm and way too deoxygenated for Longfins. Nonetheless, two Longfins were caught, one each, in water temperatures of 74.7 and 77.9 degrees F. The Longfin caught on Sunday was in low DO too. (I believe both were young-of-year.)

- According to Hobbs and Moyle (2015) : Adult Longfin Smelt are rarely found in water warmer than 64º F and young-of-year are rarely found in water above 73º F.” https://www.wildlife.ca.gov/Conservation/Fishes/Longfin-Smelt

- Are Longfins becoming year-round-residents here? Is that even possible?

Golden green Anchovies.

Anchovies continue to be a bit of a paradox. They generally live in the deep blue Pacific where waters are cold and relatively oxygenated. Nonetheless, they are regular summertime inhabitants to our warm, and practically anoxic, marshes.

I go so far as to say, they are like heat-seeking missiles for low DO: about half of the almost 800 Anchovies of August were caught at stations with low DO.

Blue, gold, and green Anchovies.

You know what else is strange? When we catch Anchovies in low DO, as in Pond A21 this day, they are very listless and fragile. Many do not survive the rigors of being netted. They seem to be on the verge of suffocation.

In higher DO water, they are energetic: They jump out of your hand if you don’t hold on to them.

Why do Anchovies routinely accept discomfort and stress of entering low DO water? (We don’t find dead anchovies, so survival is not the issue.) The attraction must be food, sex, or both. Does anyone else have good ideas about this?

Anchovy Photarium Experiment. I performed the above experiment last month, in July, when DO was high. Even under the best conditions, Anchovies simply must continue to “Ram Ventilate” (https://socratic.org/questions/588b5ce0b72cff17616bbf3a ) or they quickly sink to the bottom. (I have performed this test a couple of times. Results are always the same.)

I would assume that any fish with Anchovy-like respiratory physiology would avoid areas of low Dissolved Oxygen at all costs. But, they don’t.

Anchovy colors. I commented in July that Anchovies were generally browner. However, in August they trended a bit greener. I performed an enhanced Anchovy color survey this month, but I must report later when time and space permits.

2. Trouble at Station Alv1?

Green water and cornflakes at Alv1.

Green water at Alv1. Dr. Hobbs noticed these cornflake looking patches of algae which is consistent with Microcystis, a common cyanobacteria, and well-known type of Harmful Algal Bloom (HAB). https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Microcystis

We saw no harm being done here. Microcystis blooms in warm FRESH water. Salinity here was over 10 ppt. In other words, Microcystis flushes down from Guadalupe River and probably dies here (IF, this is actually Microcystis). What we were seeing here could indicate a potential problem further upstream.

However, Microcystis cyanobacteria may release “Microcystin” and related toxins as it dies. (The toxin lyses from dead cyanobacterial bodies.) We looked for any signs of sick or dead fish or birds, but we didn’t see any.

Prickly Sculpin and California Halibut from Station Alv1 – no signs of toxin.

California Halibut continue to show up despite the wet winter and spring. We have seen more young Halibut in 2019 (27 so far) than seen in all of 2018 (only 4!). But, the numbers are still not great this year.

Nonetheless, CDFW reported on Facebook that this is a very good year for larger, legal-sized, Halibut in the deeper SF Bay due to very good recruitment 5 to 10 years back (unfortunately I can’t provide a link.)

Prickly Sculpin continue to show up in numbers reminiscent of the very wet year of 2017: 299 caught so far this year versus 406 in 2017.

3. Arrow Gobies versus Cheekspots.

Arrow Gobies and Cheekspot Gobies were both caught in August – the same pair is shown at various angles.

Arrow Gobies and Cheekspot Gobies were both caught in August – the same pair is shown at various angles.

Update on Arrow Gobies versus Cheekspot Gobies. We caught both types in August, so I had another opportunity to show a side-by-side comparison.

- Cheekspots have the eponymous blue-black spot on the cheek (the operculum). But, the spot is iridescent and disappears under different lighting angles.

- Arrows have a big mouth. But, they don’t always open their mouths wide and the corner of the maxilla extending back behind the eye is very hard to see.

Same Arrow and Cheekspot Gobies in the Photarium.

Cheekspots have slightly more compact bodies. They look more designed for life on, or in, firm-to-hard substrate. What little goby literature I have found so far seems to support this view.

Arrow Goby out of, and in, the Photarium.

Arrow Gobies are more sinuous and snake-like. I assume this body shape makes them better adapted for life on shallow mudflats and in mud burrows.

Cheekspot Gobies and a Staghorn Sculpin.

In July, we found only Arrow Gobies. This led me to speculate that warm weather may favor Arrows. Wrong again! Now we are in August, the water is a tad warmer, and we found both Arrows and Cheekspots.

Note: I have satisfied my curiosity. I am NOT suggesting that the UC Davis lab attempt to differentiate Arrows from Cheekspots in the future! Field identification is way too slow and problematic. Determining ranges or ratios of these tiny and very attractive gobies is a separate labor-intensive project in itself. Personally, it interests me, but I can’t justify tormenting UC Davis researchers with this nonsense.

4. Other interesting marine life.

Staghorn in buccal-respiration mode.

Pacific Staghorn Sculpin. Staghorns are colloquially grouped with Longjaw Mudsuckers and Yellowfin Gobies as “bullheads” by anglers, who use them as baitfish, because they often appear to have large heads when you examine them out of water.

Same Staghorn (with a friend) in the Photarium.

Staghorns are not quite so bullheaded in water. The “Bullhead” is really a symptom of forcing these bottom-dwelling fish to expand their buccal cavities so they can absorb oxygen out of water. https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Buccal_pumping

They can survive quite a while in buccal-respiration mode. But, they are stressed. They don’t look calm or natural until you put them back in water. (It actually took me a while to figure this out!)

A young Crangon franciscorum shrimp and some Ceramium red algae from LSB1.

Crangon. Only 2246 Crangon were caught in August, a drop from over 6000 in July. This is not the big population bounce we were hoping for. Crangon numbers are still well ahead of non-native Palaemon and Exopalaemon shrimp. I continue to hope we will see a big Crangon population surge before December.

Ceramium. Once again, Ceramium appears to be in bloom at most downstream stations. This is the small, very fine, thread-like red algae. ( https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Ceramium ). Our variety may be Ceramium pacificum, http://www.seaweedsofalaska.com/species.asp?SeaweedID=61, perhaps? Ceramium is one of several types of red algae from which agar, a food extract, is produced. It’s good, highly edible, stuff according to all I read.

Orange-Striped Green Anemone??? (Diadumene lineata). We again found a number of these tiny (roughly 1 cm) orange anemones peppered over oyster shell hash at the LSB stations. If my identification is correct, this is a non-native Asian species that has been on this coast for several decades. https://www.exoticsguide.org/diadumene_lineata

However, I am not certain about the identification. This anemone is the right size and looks like D. lineata in most respects. But, D. lineata is mostly green with thin orange stripes. This one is practically all orange. There is a bit of green between the orange stripes, but you must look hard to see it.

5. Polychaete Battle! Clash of the Early-Cambrian Titans!

Polychaete Face-off. As we cruised down Alviso Slough from Alv1 to Alv2, two of our captured Polychaetes interacted as I watched. I had read that Nereid Polychaetes can display territorial aggression. Nonetheless, I was taken aback by this display of raw violence.

Big worm, to the left, is showing a pair of much larger sharp palps. Little worm, on the right, is out-classed. Apparently, palps are the polychaete primary weapon. This too surprised me. These polychaetes have a proboscis with a pair of hard pincer-like jaws that they can project from the esophagus. But, the jaws did not come out. This fight was all about the palps.

Reminder: These Polychaetes are “Alitta Succinea” https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Alitta_succinea, aka, “Rag Worms,” “Pile Worms,” “Clam Worms,” etc. … at least as far as I can tell.

Pow! The two worms made initial mouth-to-mouth contact. After the break, it was clear that the worm with the bigger palps was going to dominate the fight.

As little worm beat a hasty retreat, big worm bit him mid-body. Little worm reacted to the bite like it was an electric shock. Literature tells us that some polychaetes have venom glands connected to the palps, and this is evidently true in this case.

(I was going to say they made “face-to-face” contact, except that polychaetes don’t have faces. The “Prostomium” is the first body segment which has the palps, tentacles (at least three pair in this case), and eyes. To my human eyes, the entire prostomium looks like an upper lip. The mouth comprises a sort of lower lip. https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Prostomium)

Another genus of Polychaetes, Glycera (aka Bloodworms) are well documented to have venom which they use to kill prey, albeit Bloodworms inject venom from jaws, not the palps, from what I see:

- https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Glycera_(annelid)

- An article about Bloodworms and venom: https://www.nationalgeographic.com/science/phenomena/2014/09/10/the-venomous-cocktail-in-a-fishermans-bait/

- Interesting video about hunting polychaetes for bait in Maine: https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=o7aM5gU8mFY

Second bite. After the first bite, little worm was done fighting, but big worm kept chasing him down. The second bite is shown above. There appears to be a gelatinous substance emanating from one of big worm’s palps, but it could be debris.

Final outcome: little worm was totally vanquished. With no avenue for retreat, he assumed a defensive stance. At this point, I had to dump the worms back into Alviso Slough. I couldn’t support further worm cruelty.

This episode raises questions in my mind:

- How acute is Polychaete vision? I assumed that the two pair of eyes sensed light and dark, and little else. A dweller of the murky mud-bottom should not need good vision. But, these two polychaetes appeared to see, and strike at, each other with clarity. There may be some chemical senses involved, but I think vision plays an important role.

- How intelligent are Polychaetes? These two Polychaetes recognized their own kind and evaluated each other for a battle. Each one figured out quickly where he/she stands on the pecking order. Intelligence like this does not surprise me in fish, birds, mammals, insects, and crustaceans. But, these are worms! These organisms are several evolutionary branches and a few hundred million years removed from all the rest of us! They have more brain than I realized.

- Polychaetes feel pain! (This is an observation; not a question.) I was told as a kid that worms don’t feel pain when you bait the hook. That is incorrect! I saw little worm react violently when big worm bit. They feel pain! Look at the photo above: Little worm “knows” he/she is about to get bitten again. Big worm “knows” he is the biter. They feel pain, and they remember it.

6. Time out for Marsh: “Turn off your mind, relax, and float down stream.”

Detour into Pond A6, aka “the Duck’s Head.” Pond A6 is located just below center of the Trawl Map, far above. This former salt pond was breached for passive restoration in 2011. Tide was just barely high enough near mid-morning to allow us to briefly motor in to see how restoration is progressing.

In most respects, the appearance here is similar to Pond A19 which was similarly breached in 2006.

Marbled Godwits in Pond A6.

On this particular morning, the pond was mobbed by Marbled Godwits. These are one of several types of shorebirds that eat small crustaceans off the mudflats when tide is low.

Before restoration, Pond A6 was a notorious nesting place for tens of thousands of unwanted gulls, so this is a good change. (However, the gull problem persists in our local landfills.)

- https://www.allaboutbirds.org/guide/Marbled_Godwit/overview

- https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Marbled_godwit

Before and After. Top photo taken in 1993. Bottom photo from August 2019.

A 26-year difference! I took the top photo from one of our SJ-SC RWF helicopter-based water quality monitoring surveys back in 1993. This past weekend, I took a new photo shot from roughly the same angle. I tell people, that it used to be a “Brown Bay” when I first started working here. I watched it evolve into a “Green Bay.” Here again is the proof. The two photos show the shoreline along the north bank of Lower Coyote Creek at the foot of two PG&E towers across from Alviso Slough.

- There was very little plant life in 1993 – it was a vast mudflat extending westward to Calaveras Point. (Also, note the group of around 15 cinnamon-colored Harbor Seals on the shore in front of the towers in the 1993 picture.)

- Today, the entire area is practically covered in dense vegetation.

Bald Eagles and Ospreys near the confluence of Alviso Slough and Lower Coyote Creek.

As I watched Cheekspot Gobies in my Photarium, Micah shouted out that a Bald Eagle was circling overhead. There were no Bald Eagles in this area in 1993. This eagle is one of the two that nest in Milpitas.

Minutes later, Micah spotted two Western Osprey on one of the PG&E towers. One had a big fish.

This place is so different from what I remember in the early 1990s.

Harbor Seals near tall stands of spartina.

Harbor Seals still lounge on the mud beaches a little further downstream. There is a lot more spartina now.

Top panel: Aerial perspective of Lower Coyote Creek 1993 vs. 2019. Bottom panel: Giant mud chunks.

On the southern bank, what was once a subtidal mudflat has grown into marsh well above the Mean High Tide elevation. I distinctly remember seeing a mudflat here that only appeared briefly at low tide in the early 1990s.

More significantly, parts of the heavily vegetated southern shore are eroding into Lower Coyote Creek. Mud Island itself may have gone from sediment sink to sediment source in less than 30 years. Is this a Blue Carbon success story?

(I definitely saw giant mud chunks just upstream of mud island. I am not certain if mud island itself is sloughing off mud like this. I will be more vigilant next time out.)

7. Bat Rays – again!

Micah Bisson measuring and releasing two different Bat Rays at LSB2.

Bat Rays! 9 summer-time Bat Rays were caught, many fewer than in July which might have been closer to height of Bat Ray pupping season. The seven caught at Alv3 and Coy4 stations were close to baby-sized (roughly 190 x 250 mm). The two caught at LSB2, shown above, were a little larger.

Bat Rays eat clams, worms, Crangon and Yellowfin Gobies, among many other things. They are representatives of the top of the aquatic food web in our muddy marsh.

I will miss the September trawls, but I will dial in a September report no matter what! … so long as Jim Hobbs, or someone else, collects good photos and data from next month’s trawls.

Previous Post

Previous Post Next Post

Next Post